The recent election for the House of Commons was dramatic and unexpected, and the campaign was fiercely contested. But did it measure up to the drama of elections of yore?

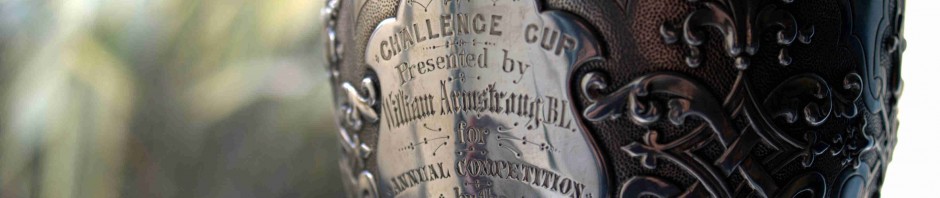

The prominent Dublin barrister Richard Armstrong (1815-1880) was the father of William Armstrong B.L., donor of the Armstrong Cup. He was M.P. for the Borough of Sligo in the Liberal interest from 1865 to 1868, and we have a vivid account of his election and the general conditions in the borough at the time from History of Sligo, County and Town by William Gregory Wood-Martin (Dublin: Hodges, Figgis, 1892).

Some excerpts:

In the election that took place on the 15th July, 1865, Macdonogh [the Conservative incumbent] was defeated, having only 158 votes to 166 recorded for his opponent, Richard Armstrong, S.L. [“Serjeant-at-Law”]

… £ 423 was distributed among voters as a consideration for their having voted for Macdonogh.

… Serjeant Armstrong expended on this election the sum of £ 2240; of this amount £ 615 was applied in defraying the legitimate expenses, £ 140 was distributed among mobs; and the residue (£ 1480) was expended in bribery.

… the number of voters so bribed amounted to ninety-seven, on an average of a little over £ 15 5s. each.

Does that sound a little different to modern practice in these matters? It was itself tame stuff compared to the following election in November 1868, in which Richard Armstrong did not stand. The candidates were Major Laurence E. Knox, then proprietor of the Irish Times, for the Conservatives, and John W. Flanagan for the Liberals. In addition to bribery on a vast scale there was considerable violence: a force of ‘340 police, twenty mounted men, two troops of cavalry, and three companies of infantry’ was drafted in and ‘was barely sufficient’. Voting was by law then open—that is, no secret ballot—and the force was necessary to prevent violence to voters and rioting. In the event one voter, Captain King, was shot dead as he approached the Courthouse to record his vote for Major Knox.

That evening Major Knox was declared the winner with a majority of 12, with 241 votes versus 229 for Flanagan. The election was subsequently challenged in court and voided by reason of bribery by Major Knox’s agents. The judge reported to the House of Commons that ‘he had reason to believe that corrupt practices and bribery extensively prevailed at this and previous elections’.

After an investigation and report—which also found intense and admitted clerical interference in the 1868 election—the House of Commons then disenfranchised the Borough of Sligo: the election of 1868 was the last one.

Wood-Martin concludes: ‘it is remarkable that the prevalence of corrupt practices in Sligo proved to have been greatest when the candidates were of the legal profession’. (This may be a matter of perspective!)

The full passage can be read here.