David’s post on the Irish Pawn Centre brought to mind the game Kavalek – Fischer, Sousse Interzonal 1967, which at one time defined the main line of the Sicilian Najdorf Poisoned Pawn.

Position after 19… fxe4

In this game, which long precedes Tony Miles’ fanciful report, White sacrificed a pawn on e5 and a knight on e4 to open lines to the black king.

Kavalek now continued 20. Qc3, and after 20… Qxa2 21. Bd1, Fischer erred with 21… Rf8?. The problem is that after 22. Bxh5+ Kd8 23. Rd1+ Bd7 24. Qe3, both f2 and c5 are covered, meeting the mate threat and also cutting out …Bc5-d4 for now. Instead 21… Bc5+! 22. Kh1 Rf8 23. Bxh5+ Kd8 24. Rd1+ Bd7 25. Rb7 Bd4 would have won, as Fischer reportedly pointed out to Kavalek shortly after the game, per the discussion here. The finish was 24… Qa5 25. Rb7 Bc5 26. Rdxd7+ Kc8 27. Rdc7+ Kd8 28. Rd7+ ½-½.

In my playing days long ago, I found a random issue of the German correspondence magazine Fernschach, I think from the late 1970s, and it contained analysis of the diagrammed position, covering White’s other tries 20. Kh1!?, 20. Qd1, and 20. Qc2 as well as 20. Qc3. The analysis indicated that 20. Qc2 was strong, with Black’s strongest response still leading to a clear advantage for White.

Engines have so completely altered the landscape that it is hard to recall just how slowly theory changed back then and how long it took to reach definitive conclusions. To give an indication, the diagrammed position appeared in a Hübner – Hort match in 1979, among other games at a high level, and close to fifty correspondence games.

One significant merit of 20. Qc2 is that it does well against 20… Bc5+ 21. Kh1 Bd4: White continues 22. Qxe4, and then, suffice it to say, Black has to find an immediate ‘only’ move to survive at all, will still have to give up queen for rook, and will still end up defending a position where White has a clear advantage. If this is not obvious as you read this, well, you have some idea of how it looked to all of us back then.

I analysed this position and Fernschach‘s analysis endlessly, and discussed it at length with Jonathan O’Connor. The problem, as we soon realised, was that after 20. Qc2, Black plays 20… Qa5, and White has nothing. Fernschach must have said something that was superficially plausible about this, but whatever it was, it didn’t hold up.

Eventually I switched to looking at 20. Qd1, and concluded that this was more promising. If 20… Bc5+ 21. Kh1 Bd4, the continuation 22. Bxh5+ Kd8 23. Rf7 seemed promising, and then if 23… Qxc4, 24. Be2 Qc5 25. Qf1 seemed unclear but playable, and I managed to convince myself that White had better chances. Alas! Engines will have none of it, and White is lost.

I told Jonathan I had found improvements, but was vague on where they were, not wanting to give it away: the improvements were “around there”, and that kind of thing. Whether Jonathan picked up on these hints is another matter!

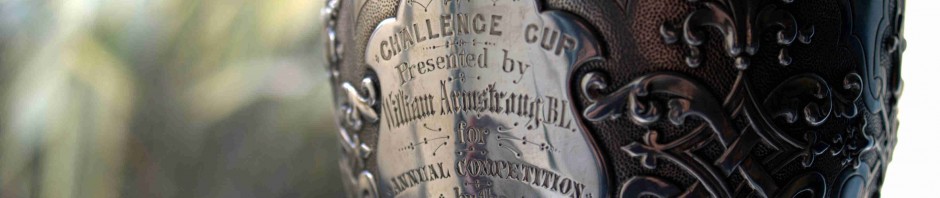

The next time we met over the board was in an Armstrong Cup match, Dundrum playing away against Dublin, in Dublin’s great premises at 20 Lincoln Place, in the 1982-83 season. We were on board 2, so I should have played Black, but by mutual agreement we swapped colours. We bashed out the first 19 moves, then after a slight pause, there came:

20. Qd1.

Jonathan gave me a searching look of unfathomable meaning, and started a long think.

20… Qa5?

This is wrong here, but the problem is buried several moves deep. After 21. Bxh5+ Rxh5 22. Qxh5+ Kd8 23. Rd1+ Kc7 24. Qe8 Qc5+ 25. Kh1, we reached the second diagrammed position, which was within my preparation, and now what can Black play?

Position after 25. Kh1

If 25… Rb8 26. Rd7+ and mate next move; similarly for 25… Ra7. On 25… Bf6 (or … Bg5 or … Bh4), 26. Rh3 is decisive. The best chance seems to be 25… e3, but White is still winning after 26. Rxe3. Jonathan, running out of time at this point (the time control was a straight 36 moves in 90 minutes), played 25… Bd6, and after 26. Rg3, he resigned (26… Qb6 27. c5!).

[Click to replay the full game.]

I wonder if 20. Kh1!? is playable?