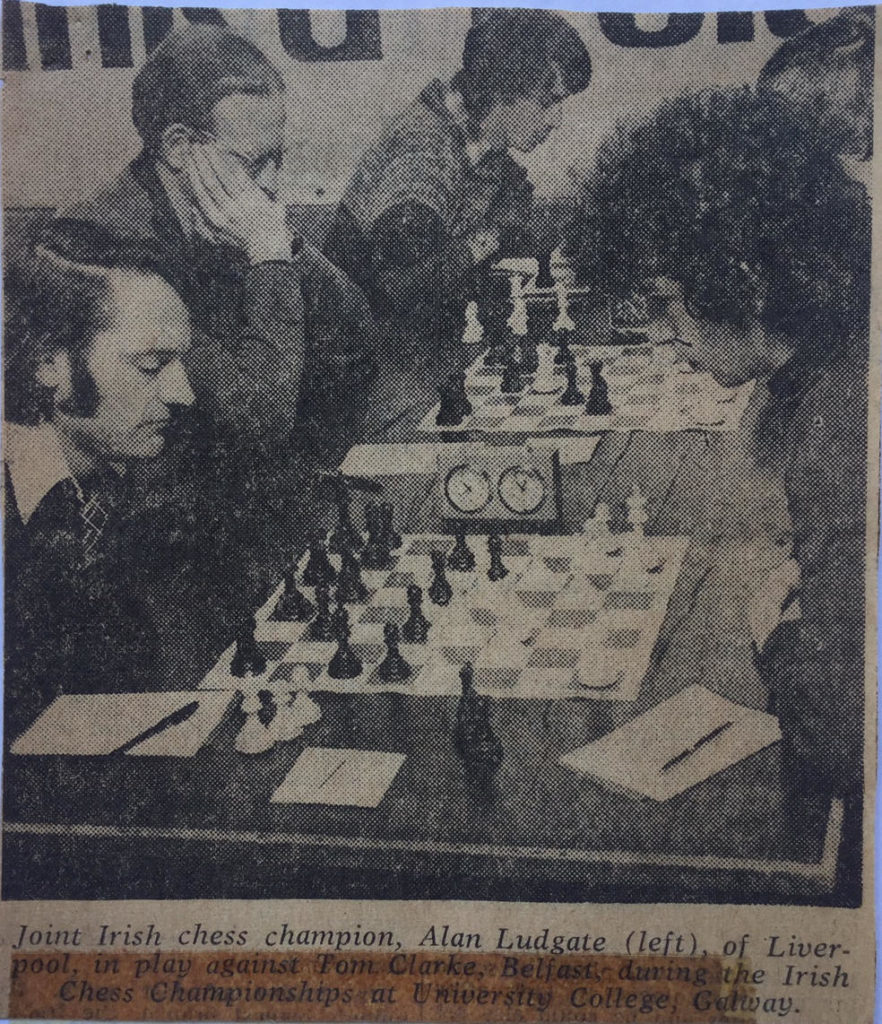

Going into the penultimate round in the 1978 Irish championship, Alan Ludgate led the field, half a point ahead of Colm Barry and Eugene Curtin, and a full point ahead of Conor Barrington and Michael Littleton. In round 8, Ludgate had Black against Littleton, and another game featuring swings of fortune resulted. Littleton built up a clearly better position, but misplayed it and allowed exchanges leading to what should have been an equal ending. The critical moment came in the diagrammed position:

34. ?

Black has just played 33… h5, and Littleton responded with the disastrous 34. Ke3??, going into a lost pawn ending after 34… Bxe4 35. Kxe4 Ke6. The only remaining possible twists involve breaks by b4 when Black tries to infiltrate on the king-side. Littleton had less than five minutes to make move 40, and this must go a long way towards explaining what would otherwise be a very puzzling decision.

From the diagrammed position, White has a fairly obvious way of holding via 34. Bc6, since after 34… Bb1 35. a3 Bc2 36. Ba4 g5 37. Ke3 gxh4 38. gxh4, Black has no way to break through.