Maurice Kennefick came to the fore in the late 1960s when he was an undergraduate student at University College Cork. In the course of the 1965-66 season, his first year at university, he rapidly moved from the junior ranks to the senior ones.

He soon became a prolific tournament winner locally, with three consecutive victories, two of them shared, in the Plunkett Trophy (the Championship of Cork) from 1967-69. He won the 1968 South Munster championship, eventually prevailing over Bill Ireton after the third two-game play-off. Also in 1968 he shared first place with Littleton, Coldrick and Haughey at an eighteen-player tournament in Limerick.

In January 1969 Kennefick had one of his biggest career wins at the inaugural Mulcahy Memorial. The Irish Universities Team Championship in Cork, in which Kennefick had played for UCC, had immediately preceded the Mulcahy and the Varsity Individual Championship was incorporated into the Mulcahy, so Kennefick had the unusual distinction of winning two titles from the one event.

From that period I have located three individual Kennefick victories, all sourced from the Cork Examiner, which do not seem to have previously worked their way into the databases.

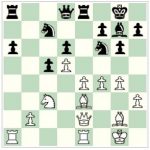

Position after 14…Kf8

Maurice Kennefick – Brian Desmond

Cork, 1967

Play through the game

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.exd5 exd5 5.Bd3 Qe7+ 6.Nge2 c5 7.0-0 Bxc3 8.Nxc3 Be6 9.Re1 Nf6 10.Bg5 Qd6 11.Nb5 Qb6 12.dxc5 Qxc5 13.Bf4 Na6 14.Nd6+ Kf8 [Diagram] 15.Rxe6 fxe6 16.Qe2 Nc7 17.Re1 Qb6 18.Qf3 Rd8 19.Qg3 Rd7 20.Be5 Nce8 21.Nb5 a6 22.Nd4 Nc7 23.Qf4 Rf7 24.Bxc7 Rxc7 25.Nxe6+ Kf7 26.Qxc7+ Qxc7 27.Nxc7 “and wins” 1-0

Position after 18…Nf6

Maurice Kennefick – John Donoghue

Plunkett Trophy, Cork, 1968

Play through the game

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 c5 3.d5 e6 4.Nc3 exd5 5.cxd5 d6 6.e4 g6 7.g3 Bg7 8.Bg2 0-0 9.Nge2 Na6 10.0-0 Nc7 11.a4 Bd7 12.h3 b5 13.axb5 Bxb5 14.Re1 a6 15.Be3 Re8 16.f4 Nh5 17.g4 Bxe2 18.Qxe2 Nf6 [Diagram] 19.e5 dxe5 20.fxe5 Rxe5 21.d6 Ncd5 22.Qf2 Qxd6 23.Bxc5 Rxe1+ 24.Rxe1 Qc6 25.g5 Nd7 26.Bxd5 Qxc5 27.Qxc5 1-0

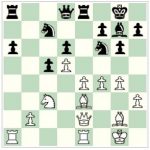

Position after 26…b5

Maurice Kennefick – Charlie Barnwell

Mulcahy Memorial, Cork, 4 January 1969

Play through the game

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Bg5 Be7 5.e3 0-0 6.cxd5 exd5 7.Bd3 c6 8.Qc2 h6 9.Bh4 Nh5 10.Bxe7 Qxe7 11.Nge2 f5 12.0-0-0 Be6 13.g3 Nd7 14.Nf4 Nxf4 15.gxf4 Nf6 16.Kb1 Qd7 17.Ne2 b6 18.Ng1 c5 19.Nf3 c4 20.Bf1 Ne4 21.Ne5 Qb7 22.f3 Nd6 23.Rg1 Rfc8 24.Qg2 Kh8 25.Qg6 Re8 26.Bh3 b5 [Diagram] 27.e4 dxe4 28.d5 exf3 29.dxe6 f2 30.Nf7+ Qxf7 31.exf7 1-0