John Moles’ book The French Defence Main Line Winawer (Batsford, 1975) has been widely praised but even still Wolfgang Heidenfeld’s assessment ‘perhaps the best of all chess opening monographs’ (see the last post) is startling, I confess. On the other hand a quick search turns up a comment by John Cox from recent years that includes the book as one of his all-time top three, so this opinion is not an outlier. Some of you may wonder what could possibly justify such an evaluation.

The chess world of September 1974, when the writing was finished, is so far removed from today’s that it’s easy for the modern reader to be misled by Moles’ description of the book’s scope: ‘as complete and up-to-date a survey as possible of the main lines of the Winawer’. He set out to cover not only the full list of variations in the main line (1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 e5 c5 5 a3 Bxc3+ 6 bxc3), itself a daunting task, but also to include all relevant games, and reflecting all associated analysis and commentary: a “complete” survey indeed. This required a herculean research effort even then, with ‘countless [the inside front jacket says over 3,000] theoretical hand-books, game collections, tournament books and bulletins and magazines’ consulted. The results surpass modern databases in many variations.

The insistence on coverage of all the possibilities, coupled with Moles’ willingness to delve deeper than his contemporaries, often generated conclusions that contradicted the prevailing wisdom of the day. Here is one example.

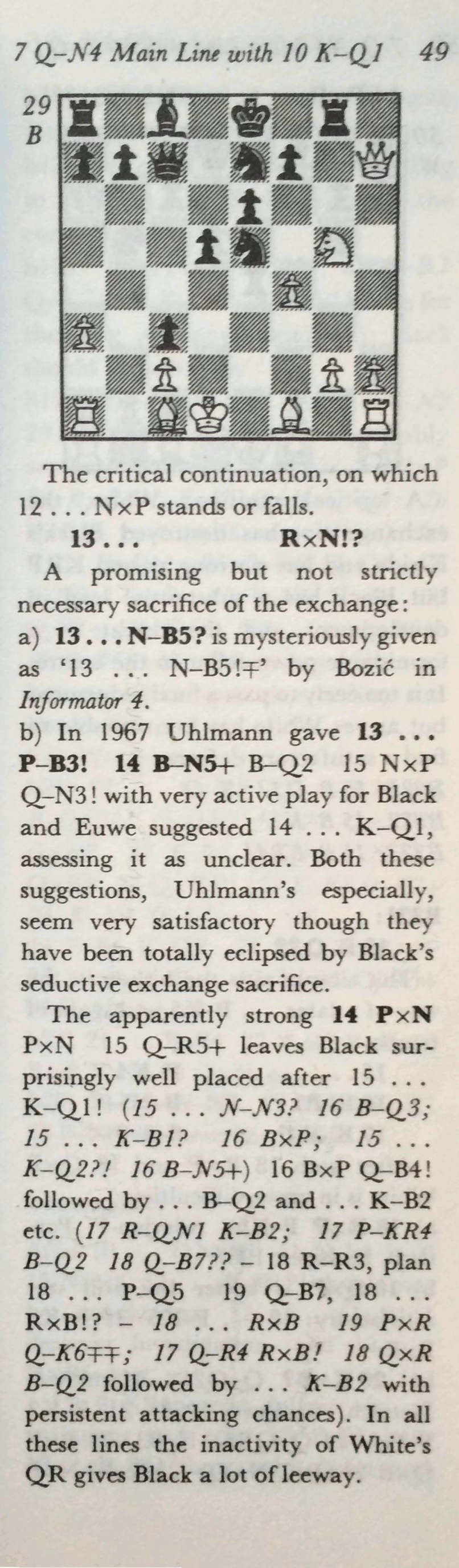

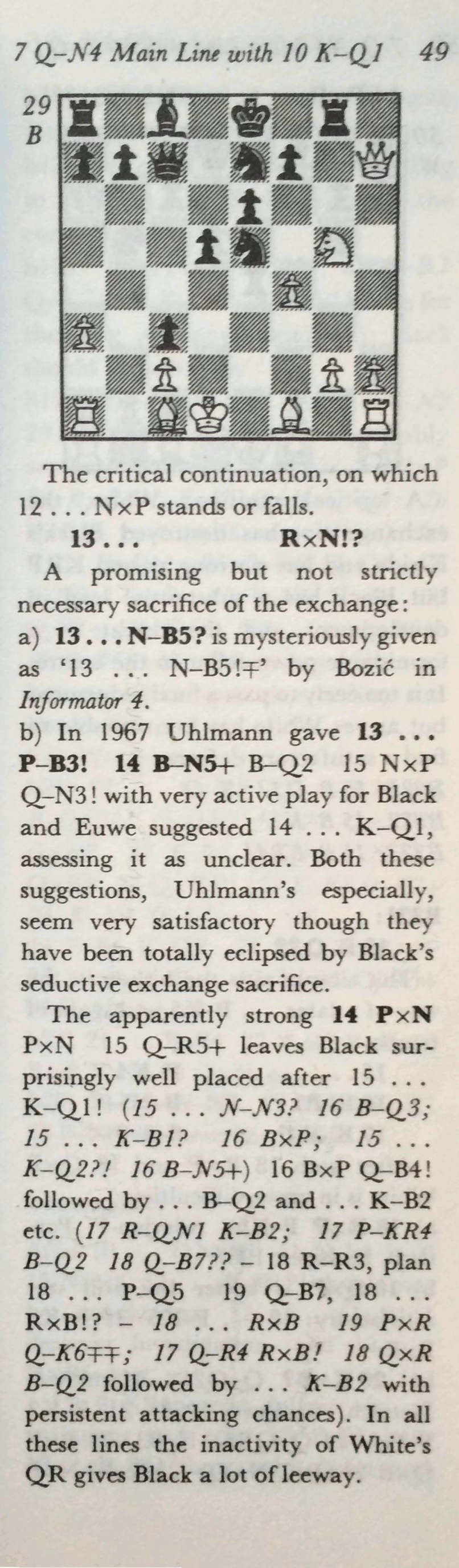

In the main line Poisoned Pawn, after 6 … Ne7 7 Qg4 Qc7 8 Qxg7 Rg8 9 Qxh7 cxd4, the rare but sharp and critical line 10 Kd1 Nbc6 11 Nf3 dxc3 12 Ng5 Nxe5 13 f4 (see diagram below) leads to a position on which Emanuel Berg, in his Grandmaster Repertoire 15: The French Defence Volume 2 (Quality Chess 2013) spends ten full pages (46-56). The important point for Black to remember here is to avoid the natural, thematic, and tempting 13 … Rxg5!?, and instead play the odd-looking 13 … f6!.

It’s no exaggeration to say that 10 Kd1 is rare today in significant part because Black has 13 … f6 here.

Anyway, here’s what Moles has to say:

And that’s it, other than a line at the end of chapter giving 13 … f6! as ‘the sounder choice’.

There the matter rested for five years until Popovych–Watson, Bar Point International, New York 1980, in which White was demolished (0-1, 25). This was the first over-the-board trial of 13 … f6! (there had been two unpublished correspondence games in the late 1960’s) and the first of any type featuring the analysis in Moles’ last paragraph, which is now the main line. The game received wide publicity, appearing in both Europe Échecs (September-October 1980) (Caminade) and Chess Life (December 1980) (Benko).

The game featured in Watson’s Play the French (1984), along with two more of his own games, and then in two games in 1985 that appeared in Informator. From there was included in virtually every openings book as the (or at the very least a) standard response, which is the status it enjoys today.

Other books of the era missed this. Only Zeuthen & Jarlnæs (1971) mentioned it at all, giving Euwe’s analysis, i.e., 13 … f6 (14 Bb5+ Kd8 ∞), and saying it had never been played. It’s missing entirely from the books by Keres (1969 and 1972), Gligorić & Uhlmann (1975), Suetin (1982) and Zlotnik (1982), and from Encyclopedia of Chess Openings C (1974 and 1981). And similarly for periodicals.

There’s a twist to this story that has never been commented on. Contra Moles, I believe that Uhlmann never suggested 13 … f6. Instead it was Trifunović who recommended it in 1967 Chess Review 35/12, December 1967, pp. 380-81, considering only the (weaker) 14 Bb5+, and giving the analysis that Moles credits to Uhlmann. And when Trifunović later considered 14 fxe5, he promptly withdrew his original recommendation: ‘13 … f6, suggested by this writer, leads to a quick loss after 14 fxe5 fxg5 15 Qh5+!’ Chess Review 36/10, October 1968, p. 307. Euwe’s two items in Archives (December 1967 and February 1968) go no further than his analysis as cited by Moles; the second cites Trifunović. (There’s other evidence as well.)

Whether on the basis that there must be something there if Uhlmann recommended it, or because of Moles’ general policy of searching deeply and exhaustively in all variations, I believe he looked further and found the inspired 15 … Kd8! and 16 … Qc5!.

On this reading, note the final paragraph above, which must have come entirely from Moles: he goes counter to the weight of virtually all preceding theory, introduces an excellent innovation that changes the evaluation of the variation, and provides all the essential ideas and analysis. Incidentally the ten pages provided by Berg on this line are excellent, as are the three in Watson’s Play the French, 4th edition (2012). But it’s nevertheless fair to say, I believe, that they confirm Moles’ account rather than contradicting it in any way. If you had to summarise the entire variation in one paragraph I don’t believe you could do better, even now.

And that’s one paragraph in a 258-page book …